The minimalist style, a classic of modern design, was obviously one of the first topics covered in this blog. What we tried to offer, more than the usual summary of the characteristic elements of the style, was an interpretation of the ambivalence hidden behind the minimal philosophy: on the one hand the modern utilitarian and materialist aspect, on the other, the traditional austerity.

In short, we have highlighted how the minimum can mean a reduction in space and costs due to material needs, savings or lack of interest in complicated and profound things, in line with the modern criterion of economic efficiency. Or it can express a tendency toward the essential in an “ascetic” and spiritual sense.

JAPANESE STYLE: MODERN BUT NOT THAT MODERN

It goes without saying, therefore, that traditional Japanese style, according to aesthetic criteria, is considered by many to be the archetype of modern style.. But it is inevitable to observe that, in Japanese spaces, the aesthetic aspect is only the crust of this spirituality. Furthermore, it is possible to notice that there is a difference between strictly religious spaces, normally more baroque, charged and colorful, and Japanese spaces that, on the other hand, speak from the simplicity of a spirituality that is direct experimentation and “Spartan” representation.

The experience is only minimally visual, therefore it induces introspection. One observes oneself, with the help of a simple environment that, at the same time, transmits peace and harmony: light wood, bamboo, natural light, plants and vegetation, paper, stone and light fabrics. It is no coincidence that, for example, Japanese rural houses, with the typical sloping roof, are curiously called gassho-zukuri (“joined hands”) houses due to their shape. A definition that comes from the most intimate, natural and spiritual act that exists: that of joining hands in prayer.

PURITY AND STYLE: TWO WORDS THAT DO NOT GO TOGETHER

In our virtual trip to Japan, helped by the text “Living in Japan“by Alex Kerr and Kathy Arlyn Sokol and by Reto Guntli‘s photos, we were able to take a closer look at this reality. But we have also been able to confirm that the Westernization of the country, which began with the Mejii Restoration and, more generally, the “natural” process of globalization (standardization) of aesthetic taste and construction and decorative techniques, has obviously left very few things intact. and original. Traditional Japanese minimalism has become contaminated with Western modernism. But, above all, we must not forget that the Japanese style, today, is precisely a style. And it is as such that today we talk about it in a design blog.

What does it mean? If in the past it was built and decorated in a certain way out of necessity, taste and tradition and the difference was “spontaneous”, today it is limited to copying or more or less artificially preserving a style, for tourist or artistic-cultural reasons.. Nothing new and nothing that doesn’t happen in other areas. But it is necessary to take this into account and, perhaps, be able to appreciate the authentic continuity of some places more than others where artificiality or pollution predominates..

CHIIORI, THE BEGINNING OF OUR JOURNEY

That’s why we start our journey from Chiiori, a charming farmhouse built around 1720 in the Iya Valley (Shikoku Island), surrounded by Japanese cedar trees (sugi): “Even today it is a remote place, where thatched houses stand “They rise into the bubbling abysses of clouds and mist.” Despite an “invisible” repair and modernization carried out in 2012, it still preserves the original structure, with the roof in kaya (long-leaf miscanthus reeds) and three chimneys in the floor (“irori”) for the kitchen, heating and te that have continued to take center stage for centuries. The name Chiiori (“villa of the flute”), on the other hand, is contemporary and is due to the writer Alex Kerr, who gave this name to the structure when he bought it in 1973. The exterior, without any special decorations, is all wrapped in green and wild nature: it houses firewood for the home, old farming implements and wooden benches and little else.

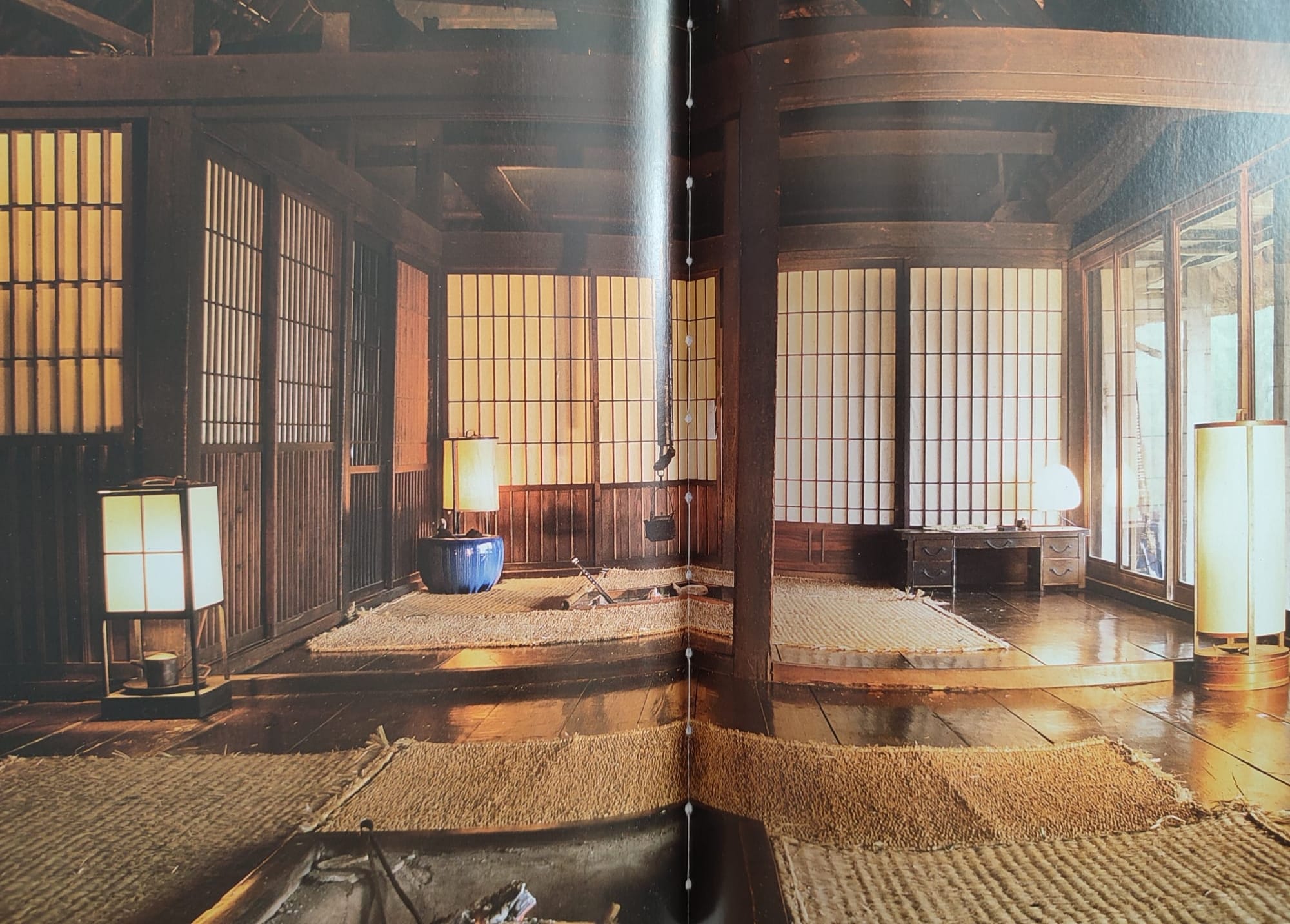

The interior is almost a single space, which refers once again to the sacredness of the temple and, in a certain sense, to the archetype of the concept of home: a shelter essentially made up of exterior walls and a roof, with a fire in the center. A model preceded only by the even more basic “tent” house, in which the roof and walls are one thing.

The entrance to the kitchen, framed in natural wood, welcomes you with a handwritten screen: “I contemplate my beloved in a corner of heaven.” Large wooden beams support the ceiling and act as internal columns, delimiting a central rectangle where, surrounded by lamps, the irori is located. The main decoration of the room is large white fabrics with black prints that cover an entire wall and refer to samurai. On the tatami floor and dark wood. In one corner, a large stone for grinding soba (buckwheat flour). In another, a low, antique desk made of dark wood, with an Akari lamp (paper lantern) designed by Noguchi. Another corner houses an iron vase with flowers, a wooden plaque with the Chiiori inscription and a small Buddhist altar.

Today this ancient Japanese “minka” has a website, is equipped with accommodation that can be booked on Booking and is the center of a non-profit organization that deals with the problems of rural areas in Japan.This remote place in Japan is not so remote anymore. Without a doubt, its meaning and identity have changed.

CHIZANSO VILLA SOUTH OF KAMAKURA

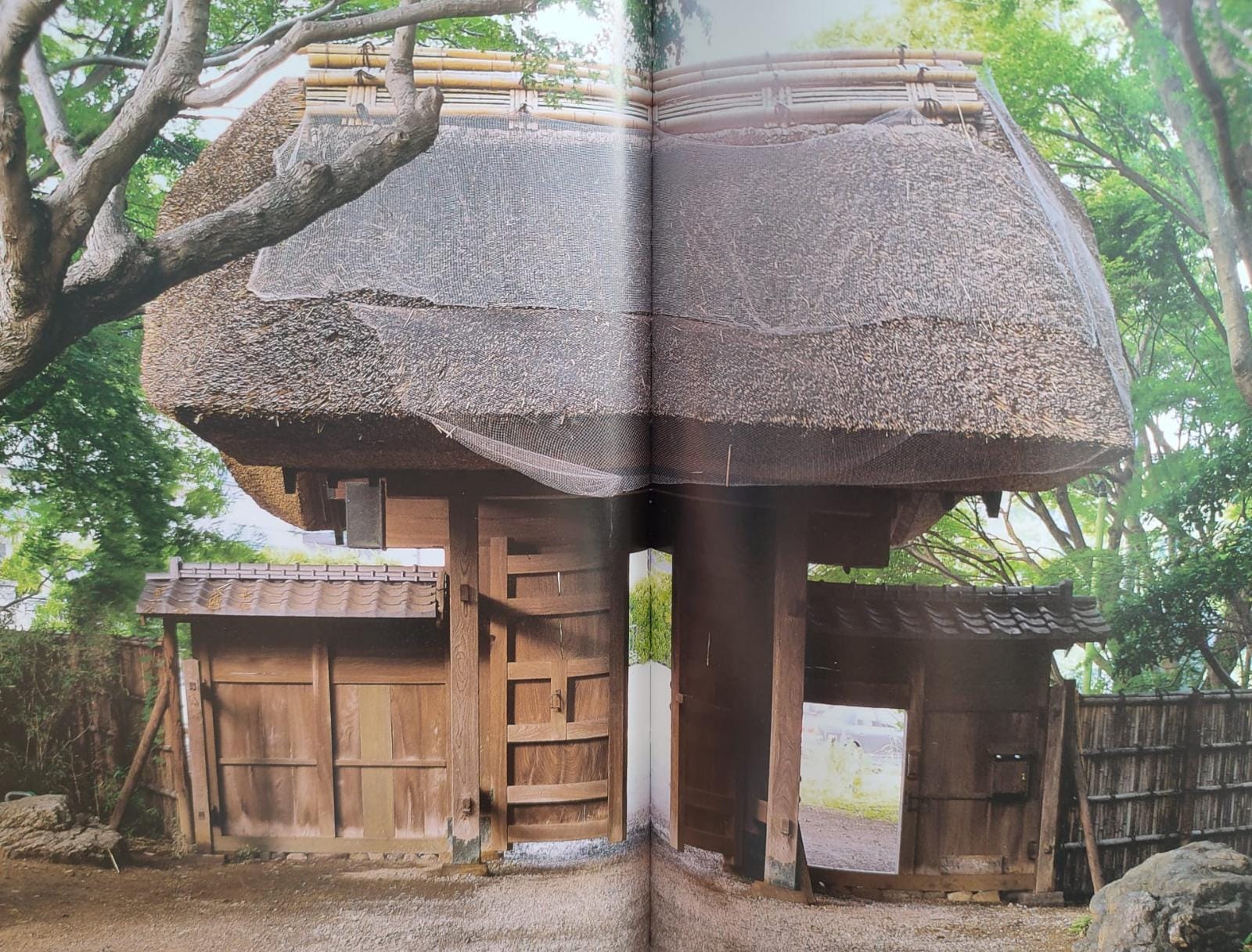

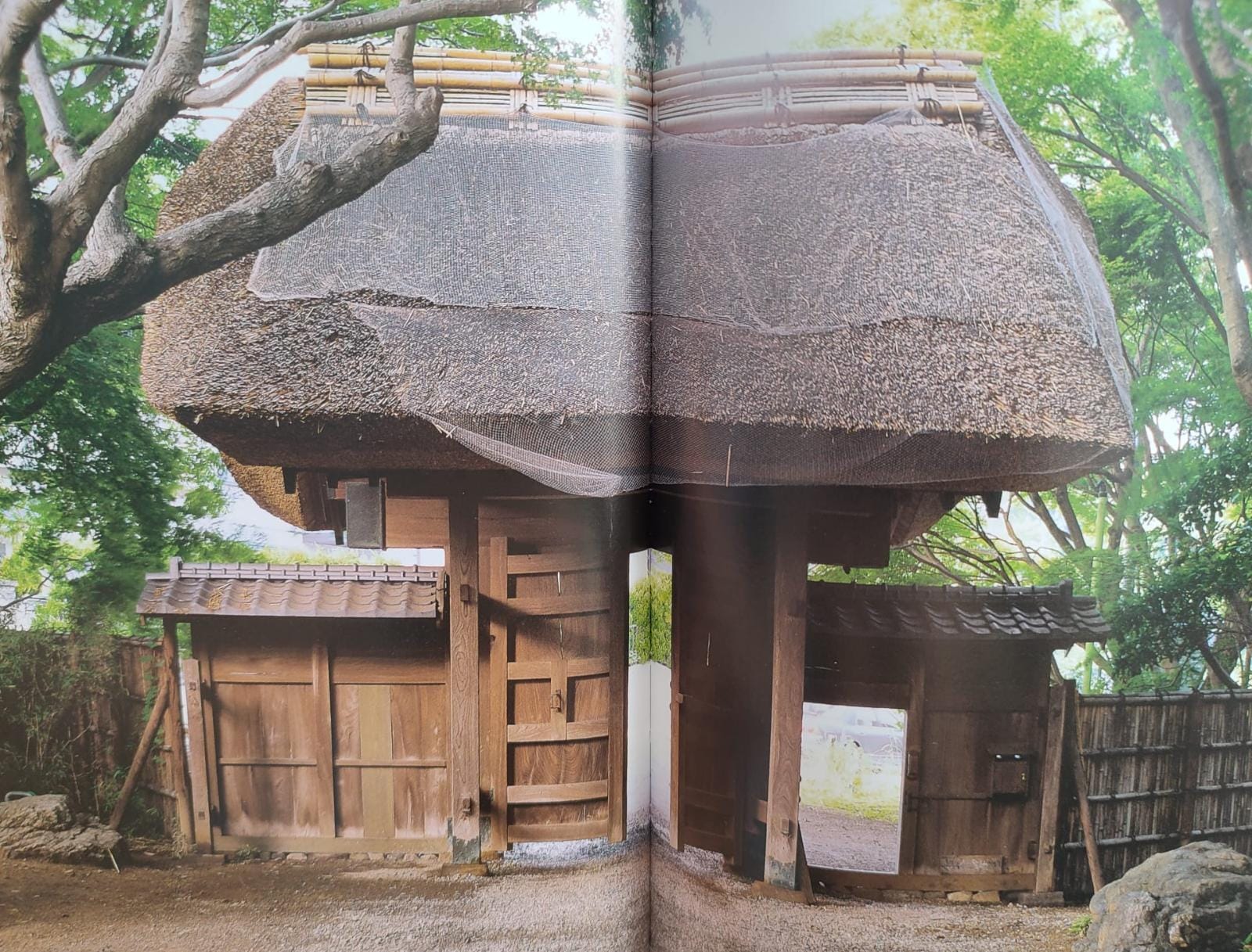

Speaking of Japanese sacredness, Yoichiro Ushioda‘s Chizanso Villa, south of Kamakura, is even home to a Zen priest (Issho) who, after spending 18 years in the United States, “transformed Chizanso into a hermitage, a place to practice Zen meditation in quiet solitude.” Chizanso, built at the beginning of the last century by industrialist Issei Hatakeyama, is one of the largest structures in an area, the hills and beaches of Hayama, that once housed hundreds of noble villas. In the complex there are a 15th century temple (the Bodhisattva Hall), a rural house from the Edo period, a house designed by Togo Murano in the 1960s and the same thatched “gate” was built in the 61st century and then transported here when the complex was built. In the kura (the warehouse) ancient tools for the tea ceremony, the traditional gong for meditation, are kept. Inside the main structure, hanging from an adjustable hook, a cast iron container above the flame of the floor hearth (the usual iori).

YOUSHIHIRO TAKISHITA HOUSE

Another Kamakura villa undoubtedly worthy of mention is the Yoshihiro Takishita House, owned by the architect of the same name, who moved dozens of Japanese minkas to the US and Argentina and who, from Gifu, in 1967 moved the latter to a hill in Kamakura. It is an impressive 18th century structure from the entrance with two large stone sculptures as guardians. In the garden, other stone statues representing the goddess of mercy, inside a large room composed of ten tatami mats, a screen with a traditional painting of a thatched house, a library with a reed mat roof and a small “mezzanine” reading room. In another room, a wonderful six-door screen with a warrior theme that represents the battle of Genpei, an elegant 18th century chair lacquered in gold and bronze, a screen from the Taisho period (1912-26) depicting two peasant women and, to its left, a wooden sculpture of the goddess of mercy. The living room has a Western-style fireplace, but the house contains many other details that make it unmistakably Japanese and beautiful. Among these, an eloquently displayed kimono, a handwritten screen that forms the backdrop to a Tibetan bronze statue perched on a Chinese pedestal.

THE “MACHIYA” OF KYOTO

After visiting Tokushima and then Kamakura, we moved on to bustling Kyoto, Japan’s capital for over a millennium (794 to 1868) and a treasured custodian of the country’s architectural history. A common dynamic can also be observed here: in the years of modernization, many machiya (city houses) were demolished. Then, however, in the 2000s, many companies sniffed out the deal and began renovating them to offer them to tourists for the “authentic Kyoto traditional house experience.”

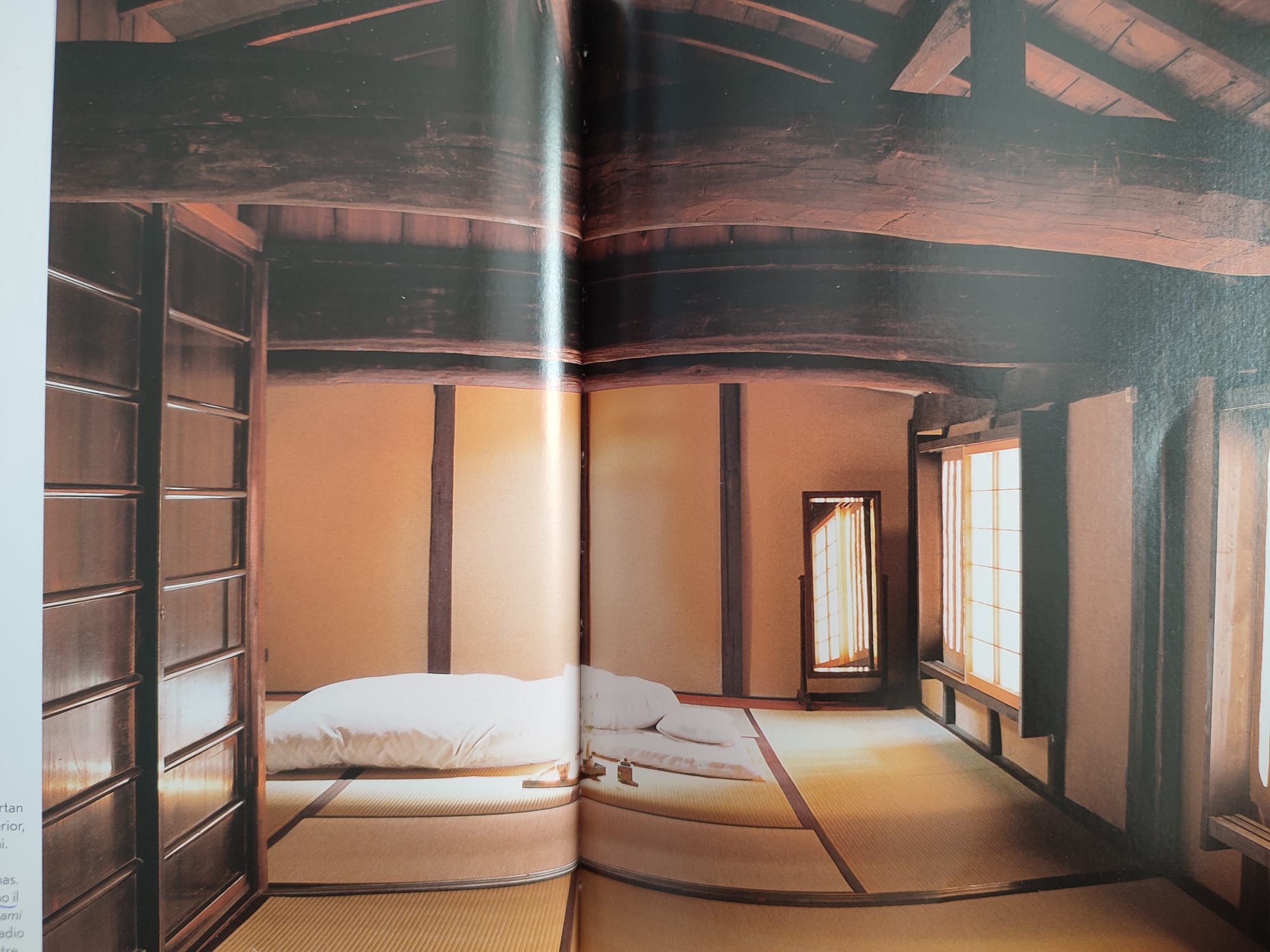

Among these, Nishioshikoji-Cho, originally built in 1890, with the classic wooden beams, the internal garden, the sliding paper doors, a collage of calligrams, fans and poems that hang from a screen form the background of an elegant porcelain vase, a large “bed” covered with mats of tatami and topped by wooden beams, a circular “marumado” window carved into the plaster of the wall reveals the reticular structure in bamboo, in another bedroom a wonderful painting from the Edo period is the background of a wooden screen.

Among the machiya, however, the greatest is Sugimoto, a mirror of the wealth of the city’s former merchant class. Sugimoto, in fact, was built in 1767 by a kimono wholesaler, although its current structure dates back to 1870. Rich in details, with a luxurious reception room equipped with “misu” curtains, the house preserves an old wooden plaque that refers to the kimono trade, a noren curtain with the ideogram sugi (cedar, derived from the surname Sugimoto) and a brass wheel with engraved character Kio (capital) and a beautiful Buddhist altar in wood, gold and metal. Entering these houses, rural and urban, is undoubtedly the most direct way to capture the essence of Japanese style without words.

Emmanuel Raffaele Maraziti